Local Trends in Global Music Streaming

Going back to the earliest forms of recorded music, technology has made it progressively easier for countries around the world to share music with each other. Recently, through streaming services like Spotify, people now have access to a global catalog of music, along with powerful tools to help them browse and explore that catalog. In our paper "Local Trends in Global Music Streaming," published at the International Conference on Web and Social Media 2020, we investigate recent trends in how countries are exchanging music in order to better understand how preferences for local and global content have possibly changed throughout the rise of streaming.

Our study focuses in particular on countries' preferences for their own, local music. Here, we define that someone is listening to "local" music whenever the recording artist is from the same country as the person who’s streaming it. Past studies into the globalization of music have adopted a similar focus, tracking countries’ preferences for local content over time to better understand the current direction of globalization, especially following the introduction of new technologies or policy interventions. As one of the most popular and easily-traded art forms, music offers unique opportunities for studying globalization.

To measure countries’ preferences for local content and align our results with past studies, we adopted a framework from the economics literature called gravity modeling. Gravity modeling gets its name and intuition from the gravitational force equation in physics, which specifies how the force between two objects depends on the masses of those objects and the distance between them. Past studies have shown that the trade flow of goods — and, yes, of music — between countries follows a very similar relationship driven by their “economic masses” (often estimated by GDP) and the geographic distance between them. Applied to music, this relationship provides a baseline for how much streaming one should expect between countries of given sizes, and identifying deviations from that baseline informs how different factors might be affecting trade. Among these factors, we paid special attention to how trade deviates when a country "imports" its own music. Past studies by economists call this quantity "home bias," and it's used to analyze trends in globalization and preferences for local content.

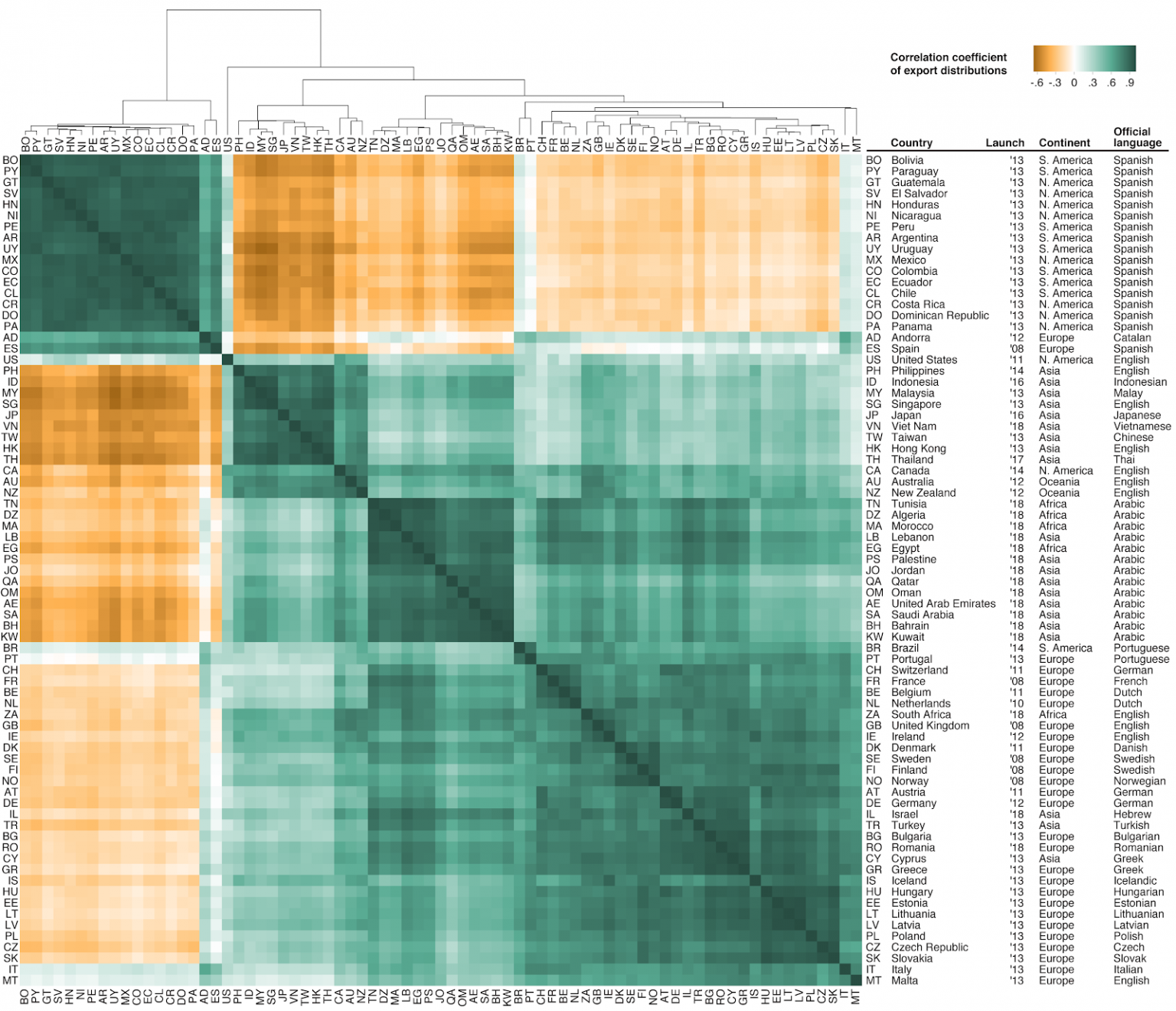

Global music exchange is strongly shaped by common official language and geographic proximity. Heatmap illustrates rank correlation coefficients between countries’ music export distributions.

Before applying any sort of modeling to the data, here’s a look at how global music trade is structured. Each element in this heatmap corresponds to a pair of countries, and the color represents the similarity (or dissimilarity) in the lists to where those countries export their music. Here, the hierarchical clustering (illustrated as a dendrogram on top) simply serves as a way to order the countries in the visualization. The structure it reveals suggests that geography and language play a major role in shaping music’s trade, and are therefore essential to include in the gravity modeling framework. With these considerations in mind, we applied gravity modeling to five and a half years of Spotify data, aggregating streams into three-month totals exchanged between importing (listener) and exporting (artist) countries.

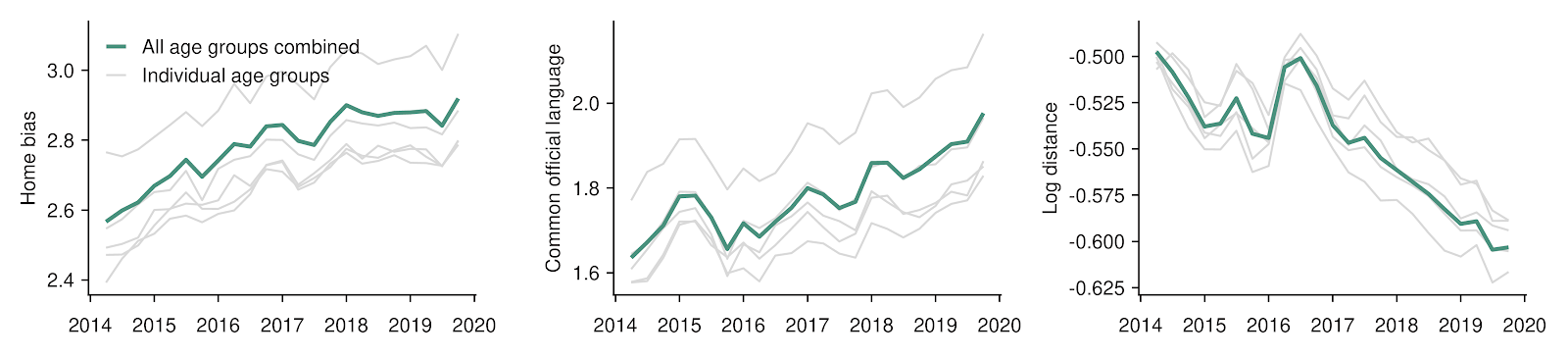

Gravity modeling reveals that countries are (left) increasingly importing their own music, (middle) trading more with countries that share a common official language, and (right) trading less with countries per unit distance.

Our results show that countries’ preferences for their own, local music (measured by home bias) have increased throughout this period, meaning more people are now listening to local music than were five years ago. This rise is possibly surprising given that the most recent research in this area found that this preference had been in decline in the years prior to our study, and also because streaming has generally increased countries’ access to each others’ music. Our results also show that throughout this same period, trade increased between countries that share common official languages and decreased between distant countries. In addition, trends for different listener age groups and across music genres all tell a consistent story: local is currently on the rise.

Of course, preferences aren’t the only component of trade that’s changed over the last five and a half years, so our study addresses several potential confounding factors. For example: the composition of who’s using Spotify has grown a lot in this period, and to the extent that more recent adopters of the service exhibit stronger preferences for local content, changes to the population of listeners on Spotify might explain the patterns above. To address this possibility, we stratified listeners by account age and found that while more recent adopters do in some cases have stronger preferences for local content, those preferences are still rising consistently across registration cohorts. In other words, after accommodating for this factor we found that the rise in local content being streamed cannot be attributed to changes to the composition of who’s using Spotify.

If countries’ preferences for local content are increasing, the natural follow-up question is “why?” In the paper, we discuss several potential explanations to motivate future studies. One possibility stems from a potential confounding factor that complicates our study and others like it: music itself also changes over time. Exactly how it changes and whether those changes affect the local “supply” and thus global demand for music remains a difficult, but essential, missing piece to the understanding of current and past trends in globalization. If true, our results here would seem to support sociologist Roland Robertson’s theory of “glocalization,” or the notion that globalization manifests through first the universalization, then the particularization of products. In that way, the current trends towards localization might not be the undoing of previous trends towards globalization but, rather, two sides of the same coin.

Or, it could actually be that preferences around the world have genuinely shifted in favor of local content in recent years. An understanding of how music itself has co-evolved with listeners’ preferences would be essential for resolving the bigger picture, as would detailed accounts of how individuals’ attitudes and preferences have possibly changed around the world. A true understanding of the globalization of music will require all corners of the music research community working together on the problem. However, considering the trends discovered by our research on streaming data, we think there’s huge progress to be made.